MARIA EISMANN

Increasing life expectancy and decreasing fertility put pressure on public pension systems around the globe. A common strategy to relieve the systems is to raise the age of pension eligibility. The Dutch public pension age used to be 65 until 2013 and is gradually rising to become 67 years and 3 months by 2021. After 2021, it is likely to rise further, as it will be linked to the average life expectancy at age 65. Moreover, once generous pathways into early retirement in the Netherlands were restricted between 2001 and 2006. Today, early retirement requires extensive private savings. These changes have a profound impact on the individual pension plans of older workers and entail special challenges for dual-earner couples.

The number of older dual-earner couples in the Netherlands is increasing due to the growing labour force participation of older women. Thus, it is no longer an exception for two working partners to stand at the threshold of retirement together. The pension system reforms affect dual earners particularly strongly if they intend to retire at the same time. Due to age differences, this often requires flexibility and coordination. However, it is unclear how many dual earners actually prefer joint retirement and which barriers they encounter. In 2015, NIDI surveyed some 2,100 dual-earner couples aged 60 and over about their plans for joint retirement.

Joint retirement

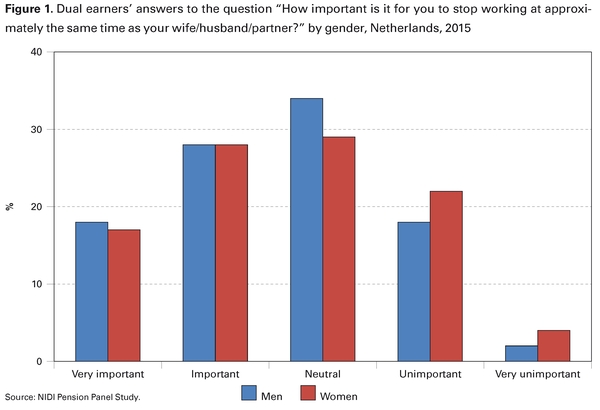

Retirement is often seen as a stage of life that allows partners to spend more time doing joint activities. Our survey shows that a majority (65%) of the older workers had clear plans to spend more time with their partner upon retirement. Possibilities for joint leisure are particularly large if one enters retirement at the same time. However, there are large differences in the degree to which dual earners evaluated joint retirement as (very) important (see Figure 1). Less than half (46%) of the dual earners of both genders thought that joint retirement was (very) important. One in five men and one in four women even rated joint retirement as (very) unimportant. Same-age couples had somewhat stronger preferences for joint retirement. Slightly less than half (48%) of the men and more than half (56%) of the women among these couples thought joint retirement was (very) important. The relatively general wish of dual earners to spend time with their partner thus does not directly translate into a wish for joint retirement. Dual earners seem to adjust their preferences when they see few possibilities to exit the labour market simultaneously.

Barriers and gender differences

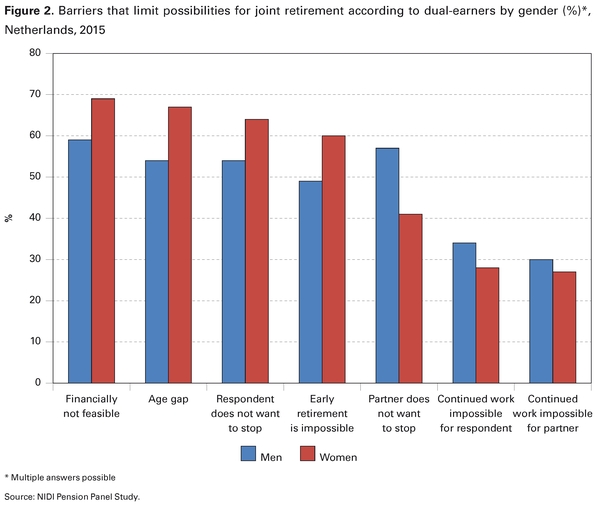

Couples were asked about the most important factors that interfere with joint retirement. Generally, they most often named the age gap between partners and the resulting financial difficulties of joint retirement (see Figure 2). However, while women most often named finances (69%) and the age gap between partners (67%), men named finances (59%) and that their partner enjoyed work too much to stop (57%) as the most limiting factors. Interestingly, women generally experienced more barriers than men did. This could be explained by the fact that the women in our sample were on average two years younger than their partners. Therefore, they reached public pension age later and were more likely to have to consider their partners’ options than the other way around. As soon as the older partner reaches public pension age, it is difficult for him or her to continue working, because workers’ contracts usually automatically end when this age is reached. For the younger partner it is relatively easier to retire early, provided that the financial situation allows this. Thus, the younger partner (usually the woman, in our sample) is often the one who needs to adapt edupension plans to the options of the older partner (usually the man, in our sample). Therefore it is not surprising that, in our sample, the women in particular seemed to experience the financial difficulties related to the age gap as a more pressing limitation than the men.

Future

The Dutch example shows that many dual earners would like to retire jointly, but that they experience financial barriers. Couples who prefer joint retirement and those who think joint retirement is less important are likely to approach retirement differently. They possibly also differ in their lifestyle after retirement. Couples who want to synchronize their retirement need to plan particularly thoroughly and take further changes in the pension system into account.

Maria Eismann, NIDI, email: eismann@nidi.nl

References

- Eismann, M., Henkens, K., & Kalmijn, M. (2017),

- Spousal preferences for joint retirement: Evidence from a multiactor survey among older dual-earner couples. Psychology and Aging 32 (8), pp. 689-697.